Tom MacInnes, Research Director, New Policy Institute.

At the start of the year, NPI produced three short briefing papers for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, with the aim of providing some of the facts and trends relating to poverty in Scotland ahead of the referendum. The purpose was to look at Scotland’s attempts to tackle poverty compared to the rest of the UK across housing, income and work.

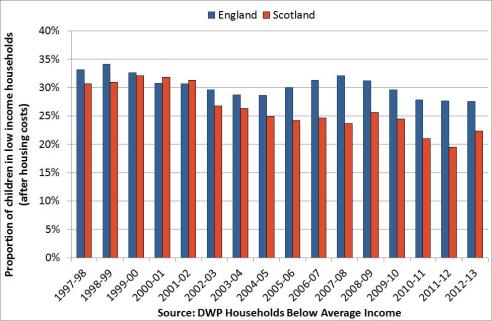

What they showed was that, in the years since devolution, Scotland had actually fared quite well compared to England, and much better than Wales. The risk of in work poverty is lower in Scotland than in the UK as a whole, and Scotland’s labour market has bounced back from the recession better than most other parts of the UK. Child poverty had fallen faster in Scotland than in England, and Scotland now has a lower child poverty rate than any other UK country. The graph below shows how in the early 2000s, Scotland and England had similar levels of child poverty. In more recent years, Scotland’s level was significantly below that of England, even if the most recent year shows a small rise.

Child poverty in Scotland and England since 1997/98

One of the reports focussed on housing and homelessness, an area where the Scottish government had substantial powers to shape a policy specific to Scotland’s needs. These powers have been used to build an approach to homelessness that is more generous than that found in England and has resulted in falling numbers of people presenting as homeless or being housed under homelessness legislation.

For all the differences between Scotland and the rest of the UK, there are of course similarities. While in work poverty may be lower, it is still rising, and set to be a feature of the Scottish social landscape like it is the English one. Scotland has more social housing, but the private rented sector is growing quickly, as it is elsewhere in the UK. With that growth come higher housing costs for tenants – the gap between social and private rental costs is greater only in London – and frequently less secure tenancies. This is a problem that the Scottish government, the UK government and anti-poverty campaigners both sides of the border have to tackle.

Over the coming weeks and months, attention will be focussed on the Smith Commission and the forthcoming white paper on new powers for Holyrood. It is too early to tell what those powers will be. In particular there appears to be a big difference between the parties on what parts of the welfare budget should be fully devolved. There is an odd paradox here – having the powers held in Scotland may result in Scottish MPs being unable to influence policies in Westminster. But having the powers is only part of the equation – they have to be used properly, and there has to be the public and political will to do so.

This was one of the bigger take-away messages from the referendum and the campaigns and conversations surrounding it. Scotland seems to have that will. Poverty and disadvantage were placed at the centre of the campaign in a way that Britain had not seen for a long time. Just as importantly, the language used was non-judgemental and did not stigmatise poor people for their poverty. So far, the Scottish government has done a good job of mitigating some of the worst effects of reforms emanating from Westminster. The challenge for Scotland is to develop this mitigation policy into one of sustained prevention. Keeping poverty at the heart of its public conversation is a good start.

For further information on research by Tom MacInnes and the NPI please use the following links:

International and historical anti-poverty strategies: evidence and policy review